Noiser

The Terracotta Army: The Eighth Wonder of the World

Play Ancient Civilisations The Terracotta Army

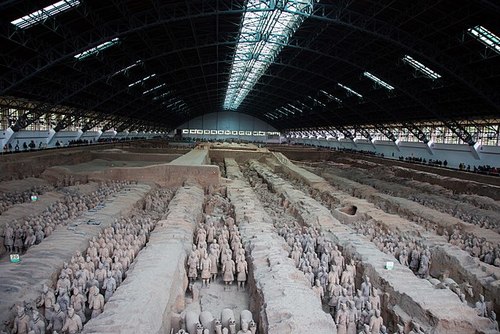

In 1974, a staggering 8,000 warrior statues were found buried in China, each one a unique work of art. But who built them, and why?

Discovery

On March 29th, 1974, thirty kilometres from the Chinese city of Xi’an, a peasant farmer named Yang Zhifa and his brothers were hard at work when they unearthed a piece of pottery. At first, they thought it was part of a kiln, but as they kept digging, they uncovered what seemed to be parts of a statue moulded to look like a warrior. Soon, they had enough clay fragments to fill three small carts, which they brought to a local museum. Little did they know, their chance discovery would lead to one of the most significant archaeological finds of the 20th century.

It wasn’t long before the authorities arrived and took over the site, displacing the peasant farmers from their land. As the experts began their excavation, it became clear that the fragments dug up by the farmers were just the tip of a significant archaeological iceberg. In the decades that followed, some 8,000 warriors were discovered, along with 130 chariots and 670 horses.

It wasn’t long before the authorities arrived and took over the site, displacing the peasant farmers from their land. As the experts began their excavation, it became clear that the fragments dug up by the farmers were just the tip of a significant archaeological iceberg. In the decades that followed, some 8,000 warriors were discovered, along with 130 chariots and 670 horses.

The First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang

The Terracotta Army is part of the vast mausoleum complex of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of unified China. This elaborate necropolis lies about a mile from where the terracotta figures were discovered.

Qin Shi Huang was born in 259 BC and was still a teenager when he ascended to the throne of China, one of the states that would form China. From the moment of his coronation, he had his eyes set on expansion. By his early thirties, Qin Shi Huang had already conquered the states of Han and Zhao, over a million square miles of territory. Next in his sights was the northernmost state of Yan. A failed assassination attempt by Yan’s leader only intensified Huang’s determination. Within six years, he had taken all seven territories, becoming the first emperor of China.

Power quickly went to Huang’s head. As well as overhauling the feudal system and introducing harsh penalties for petty crimes, he became obsessed with finding the elixir of everlasting life. Of course, no such thing existed, but his royal physicians weren’t about to tell him that. Instead, they suggested a healthy love life and, even more questionably, pills containing small doses of mercury. Over time, the effects of mercury poisoning commonly include aggression and paranoia. It was far from an ideal combination for a man who already had megalomaniacal tendencies.

The Origins of The Army

It may have been around this time that the First Emperor began work on the Terracotta Army.

Scholars are divided about the exact purpose of the thousands of clay warriors. Some see them as offering protection in the afterlife. Maybe the emperor feared his many vanquished enemies would be out for revenge after his own death. If so, he’d need an army ready to defend him in whatever realm awaited him.

It shows signs of being a military formation in a way we might expect for a functioning military division. So, certain kinds of warriors are at the front, crossbowmen are on the sides, and chariots are in particular locations to allow the leaders to issue orders. It is faithful to what we'd expect in terms of military strategy.

Andrew Bevan, Professor of Comparative Archaeology at University College London

One unconventional theory proposes a unique purpose for the Terracotta Army beyond mere representation or monument. This hypothesis suggests that the statues were part of an elaborate spiritual mechanism—a kind of artificial ecosystem designed to preserve the Emperor's life force, known as Qi (or Chi). According to this theory, the Terracotta Army might represent Qin Shi Huang's ultimate attempt to achieve immortality, not just symbolically but through mystical means.

Building an Army

It’s estimated that it took about 700,000 labourers to build the Terracotta Army. To ensure quality control over the enormous production line, each statue was stamped with the name of the foreman responsible. Craftsmen worked in small units—perhaps four or five men each. Partly as a result of this process, no two warriors are identical. Each one is an individual, carefully crafted by skilled workers rather than being mass-produced. Today, most of the surviving warriors look plain, but originally, they would have been detailed with vivid colours—red, green, purple, and blue.

This is really a huge undertaking. The largest pyramid in Giza deployed about 100,000 workers and took about ten years to complete. The first Emperor’s tomb programme employed about eight times the number of labourers used for Khufu’s pyramid project, which means that this is probably the largest tomb-building project in human history.

Eugene Wang, Professor of Asian Art at Harvard University

Qin Shi Huang may have dreamed of living forever, but ultimately, he proved as mortal as any other man. In 210 BC, at the age of 49, he passed away. He was set to be buried in his grand mausoleum complex outside Xi’an, along with his terracotta warriors, but some scholars argue that he may not have made it inside.

Huang died a long way from his supposed resting place, and with no way of preserving the body for the return journey, it’s possible his corpse would’ve decomposed and been discreetly abandoned en route. Still, the underground monument is a testament to the power of the First Emperor, a man obsessed with immortality. It would be ironic if, despite obsessively overseeing the creation of a tomb, he never actually made it inside.

Even two thousand years after his death, the great leader’s burial chamber, complete with its vast army of Terracotta Warriors, remains shrouded in mystery.